Curiosity as a performance indicator for corporate Moocs

Learning Innovation

Curious Carla and incurious Iris both completed your corporate MOOC. Good news! But, would you guess one of them will retain knowledge better than the other? Get the answer in this post, where we explore curiosity as a performance indicator in MOOCs.

Curious Carla and incurious Iris both completed your corporate MOOC. Good news! But, would you guess one of them will retain knowledge better than the other? Get the answer in this post, where we explore curiosity as a performance indicator in MOOCs.

What is it?

In the absence of a commonly accepted operational definition of curiosity, we picked the most relevant components: curiosity described as an exploratory behavior, the drive to understand new things, seeking novel stimulation, and searching for new information. The concept is strongly related to intrinsic motivation, as curiosity is a drive that does not involve any tangible reward (cf. Kidd & Hayden, 2015 (1)).

It’s quite the contrary: neuro-scientific research was able to show that induced curiosity triggers brain regions responsible for anticipated reward (cf. Kang et al, 2009 (2)).

Why should we care about curiosity in the context of corporate digital training?

While curiosity is often considered as dangerous, it seems to be an evolved trait meaning that individuals who were curious had evolutionary advantages over those not curious. Research finds that curiosity is associated with better performance, including in regard to learning. This is attributed to the very evolutionary function of curiosity: motivation for the acquisition of new knowledge. In line with this, individuals with high curiosity measures retained information better in a one to two-weeks delayed test (cf. Kang et al, 2009 (2)).

So, as you might have guessed, curious Carla from the above example would be expected to retain knowledge longer than incurious Iris.

How can we promote curiosity in the instructional design of MOOCs?

“It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.” – Albert Einstein

So, isn’t education any good for curiosity? As we overcome traditional instructional methods of Einstein’s times, we also open up ways to promote curiosity in learning settings. Here are some ideas:

- Perceptual curiosity is stimulated with UX design that uses bright and vivid stimuli, and a good dose of regular novelty.

- Epistemic curiosity is supported by self-directed learning paths, i.e. learning environments that provide the learners with a good portion of choice as to how and in which order they want to progress. This way, learners seek information that is directly useful for them.

- According to the information-gap theory of curiosity (Loewenstein, 1994 (3)), we can foster curiosity by identifying knowledge gaps and by initially providing only small amounts of information on a topic as a teaser.

- Learners are most curious on a topic or a question if they have some knowledge of it but lack confidence. (cf. Kang et al, 2009 (2)). This should be considered in the choice of training contents. Also, questions in the beginning of a course can help assess learners’ confidence level, and thus induce curiosity.

- Instructional Design should rely on curiosity-inducing tasks such as inquiry, search, experimentation, etc.

- There are ways to reward curiosity. Providing indicators inside the training platform enables L&D professionals to use this information for intelligent rewards.

What’s in the game for HR?

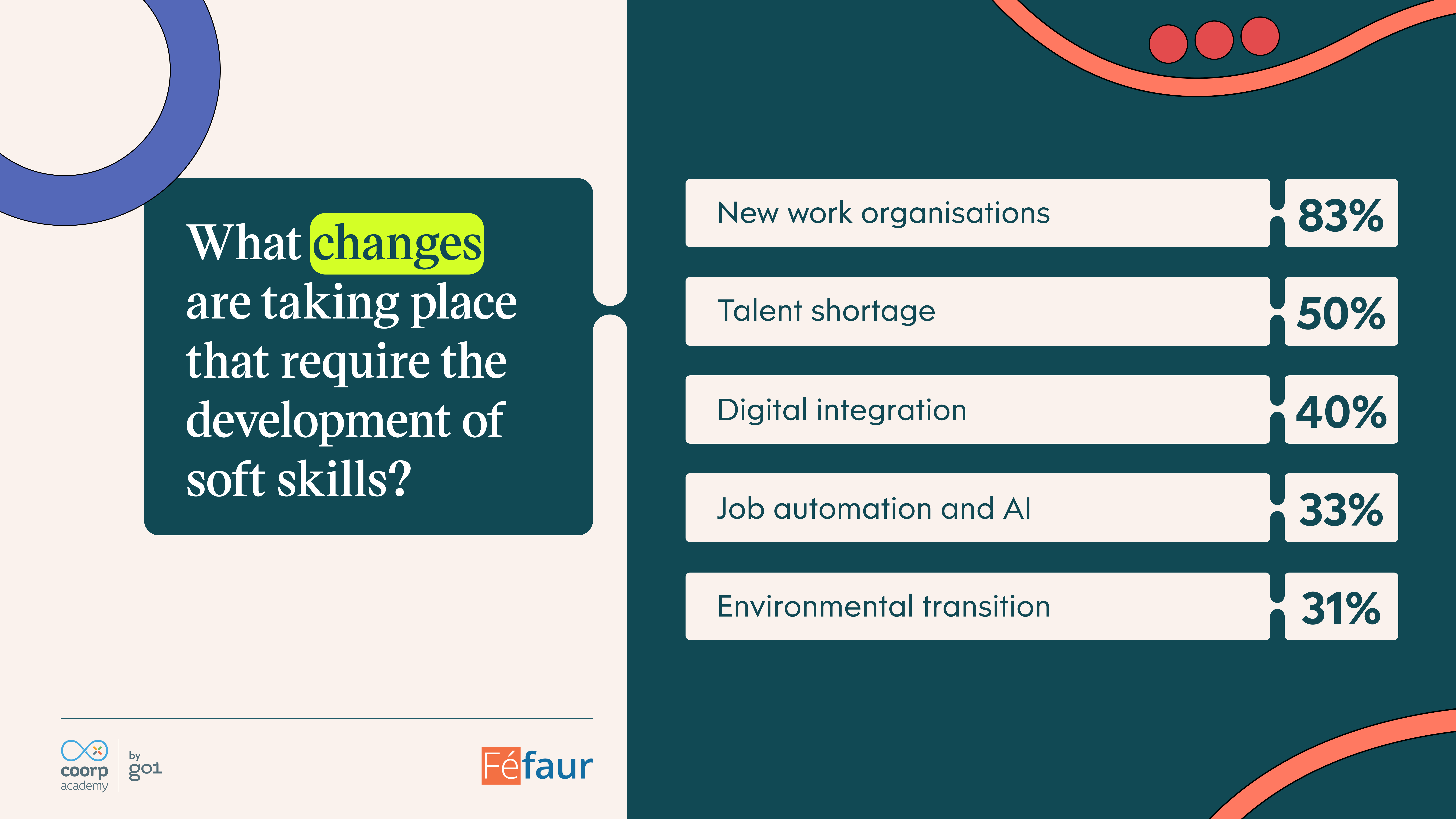

Generally speaking, curiosity is a valuable information for HR as it has been identified as an “important variable for the prediction and explanation of work-related behavior” (Mussel, 2013 (4)). Given the ever-increasing stress on employability, we can presume that curiosity will even gain in importance. The capability to engage in lifelong learning is crucial for the current workforce in order to re-skill and up-skill themselves. This helps them keep their employability high when jobs and associated skills are dramatically evolving (cf. World Economic Forum: Future of Jobs Report).

Another important effect of curious collaborators is that they contribute to a company’s innovation potential, particularly in the light of the “death of top-down management” (cf. John Bell: How Vital is Curiosity Within the Workforce?).

Edit:

We argued for the need of alternative performance indicators in the initial post of this series. Further indicators are discussed in these posts:

References:

1) Kidd, C. & Hayden, B. Y. (2015). The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity. Neuron 88, 449-460.

3) Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: a review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin 116, 75–98.