By Jessica Dehler, Head of R&D at Coorpacademy

Data, measurement, and analysis have always been important for Learning & Development (L&D). The scope, approaches, and use cases have, however, evolved a lot with the arrival of Big Data. And learning sciences and educational research are no exception to the Big Data rule, where more and more methods from data science are applied to study learning and teaching.

This article explores the evolution from evaluation-focused corporate learning to an analytics-driven one.

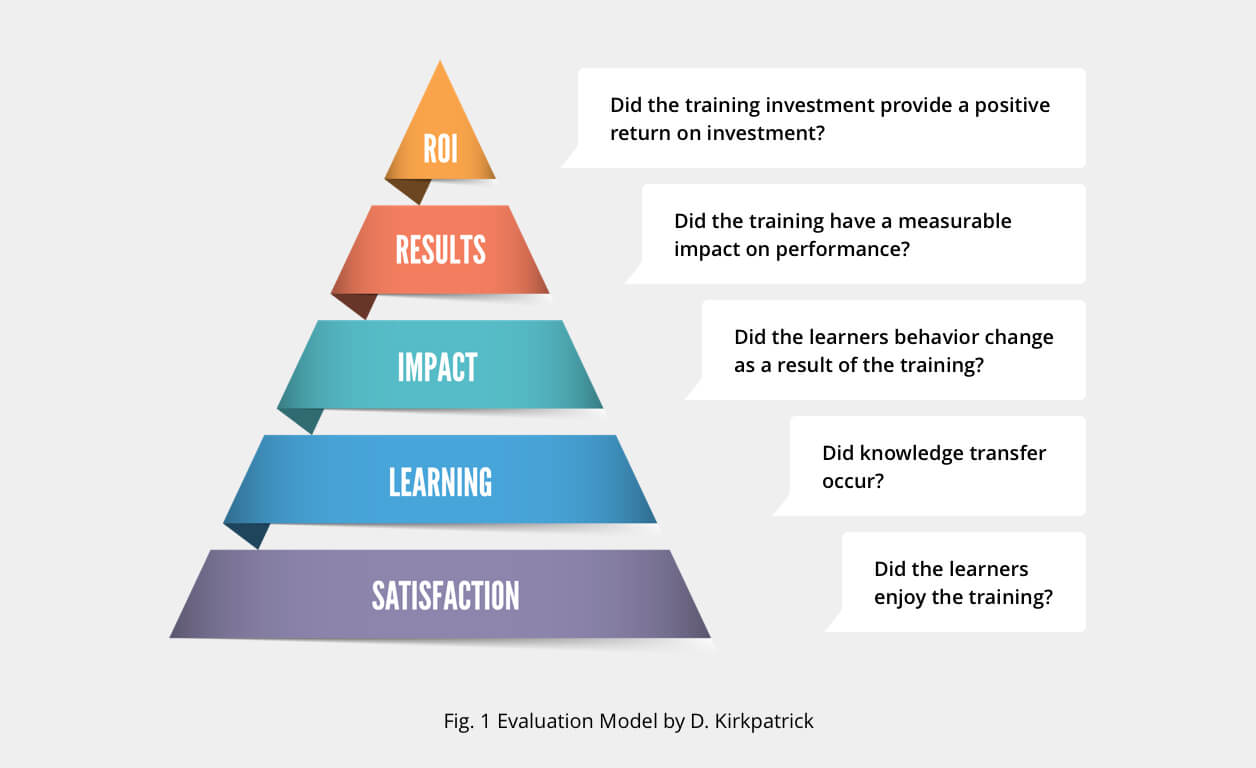

Since Human Resources and L&D in particular have adopted the role of business partners rather than mere internal service providers in their companies, they have always measured the impact of their actions. This was mainly done using a logic of evaluation and it was very often based on a model similar to the one suggested by Donald Kirkpatrick which measures the impact of training on 5 levels (see Fig 1.)

The lower levels were generally privileged because of how easy they were to measure: a combination of satisfaction surveys, completion rates and learning assessments was often considered sufficient. Analyzing only those lower levels of the model would affect the decisions and have negative implications on the usefulness of the conclusions (for a critical discussion on the Kirkpatrick model, see Bates (2004).)

This kind of evaluation, overemphasizing the “effect” in search of a proof of training effectiveness, creates a loss of interest in an age of lean processes, agile methods and continuous improvements. Today, we are looking for data and analyses that have a more descriptive nature, thereby contributing to understand learning and not simply justifying the (budget spent on) training initiatives.

L&D departments in modern data-driven organisations are getting more and more interested in analytics-driven approaches. These help to understand the “how” and the “why” of the learning that takes place during a training, to identify the needs for improvement and to develop ideas for interventions. This is not just a trend. It is deemed essential, as a significant part of the training budget is allocated to analytics (up to 5%).

This phenomenon goes along with an evolution towards new types of indicators that are measured. While completion rates were the reference metric even in the early days of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), additional indicators inform more broadly about the learners and their learning processes. The creation of these new indicators is accelerated by new ways of tracking data, such as the Experience API or xAPI which stores individual learning actions, not just data about achieved results.

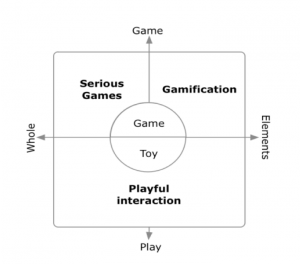

Our complete revision of analytics dashboards was intended to support our clients in this new approach. We looked for inspiration from learning analytics research and games. We discovered recruiting games designed to identify a set of performance indicators, identified as crucial for job performance based on analyses of previous employees’ performance beforehand. The game score determines the candidate’s match with the job profile. Our reasoning was that behaviour in a job-related online training would be an even more valuable source of information about a person’s qualities. We then developed a set of behavioural indicators – curiosity, perseverance, performance, regularity, and social learning – which help to understand the learners, to identify personal behavioural preferences, and to drive decisions related to communicating about and dispensing the training initiative. We benefited from the flexibility and self-directed learning on our platform, as only when learners have a certain degree of choice can their behaviour be interpreted in this way. If, for instance, the learning path was completely scripted, measuring curiosity would be impossible.

Our main challenge will now be to measure the usage and usefulness of these new insights and improve them iteratively, as can be expected in a consistent data-driven analytics approach.

References:

Bates, R. (2004). A critical analysis of evaluation practice: the Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27(3), 341-347.

Curious Carla and incurious Iris both completed your corporate MOOC. Good news! But, would you guess one of them will retain knowledge better than the other? Get the answer in this post, where we explore curiosity as a performance indicator in MOOCs.

Curious Carla and incurious Iris both completed your corporate MOOC. Good news! But, would you guess one of them will retain knowledge better than the other? Get the answer in this post, where we explore curiosity as a performance indicator in MOOCs.  Pierre Dillenbourg, Director of two labs working on digital education and MOOCs at EPFL, and Jessica Dehler Zufferey, Head of R&D at Coorpacademy, share their vision on the present and future of AI in education.

Pierre Dillenbourg, Director of two labs working on digital education and MOOCs at EPFL, and Jessica Dehler Zufferey, Head of R&D at Coorpacademy, share their vision on the present and future of AI in education.

Why do two learners with equal prior knowledge and intelligence not achieve equal results in a MOOC? Turning the question more general, why do equally intelligent persons not achieve equal results, both in terms of academic and career progress?

Why do two learners with equal prior knowledge and intelligence not achieve equal results in a MOOC? Turning the question more general, why do equally intelligent persons not achieve equal results, both in terms of academic and career progress?  Last week, Coorpacademy participated in the

Last week, Coorpacademy participated in the  In our

In our  Post initial hype about massive numbers of participants signing-up to follow MOOCs, the ensuing discussion concerned equally massive drop-out rates. Researchers and practitioners now seem to agree that completion and drop-out rates are not THE crucial performance indicators of MOOCs and their learners. They argue that many learners do not even strive to complete the course because they are interested in only a part of the course or because they want to simply watch the course material. When computing drop-out rates only for those participants who have committed to completing the course, either by paying for certification or by indicating the objective of completion in the registration form, drop-out is no longer alarming and instead close to rates in offline learning settings. (cf. EPFL(1))

Post initial hype about massive numbers of participants signing-up to follow MOOCs, the ensuing discussion concerned equally massive drop-out rates. Researchers and practitioners now seem to agree that completion and drop-out rates are not THE crucial performance indicators of MOOCs and their learners. They argue that many learners do not even strive to complete the course because they are interested in only a part of the course or because they want to simply watch the course material. When computing drop-out rates only for those participants who have committed to completing the course, either by paying for certification or by indicating the objective of completion in the registration form, drop-out is no longer alarming and instead close to rates in offline learning settings. (cf. EPFL(1))